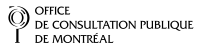

Virtual tour of the former Royal Victoria Hospital site

As a mean to familiarize citizens with the site of the Royal Victoria Hospital, the OCPM organized guided tours on September 26th, October 7th and 9th 2021. Following those tours, the OCPM created, in collaboration with Justin Bur, the guide, a text and photo summary for everyone to enjoy. Have a good tour!

As a means to familiarize citizens with the site of the Royal Victoria Hospital, the OCPM organized guided tours on September 26, October 7 and 9 2021. Following those tours, the OCPM created, in collaboration with Justin Bur*, the guide, a text and photo** summary for everyone to enjoy.

*Justin Bur, an urban planning graduate, is a writer, history researcher and Montreal tourist guide.

**All the photos from the visit were taken by Sylvie Trépanier - Photographer.

Have a good tour!

Cliquez ici pour la version française

Click on the map to zoom

1. We start in the courtyard, the main entrance to the hospital since it opened in 1893, around which the three original buildings are arranged.

The hospital is built on a rather steep part of the southern slope of the mountain.

Human presence on the mountain dates back approximately 8,000 years, not long after the retreat of the glaciers. Numerous archaeological discoveries on the island of Montreal bear witness to the activities of different First Nations over the millennia. Located at the confluence of two large rivers, the Ottawa River and the St. Lawrence River, the island is a meeting place and trading centre and, at certain times, a place for settlement.

Click on the map to zoom

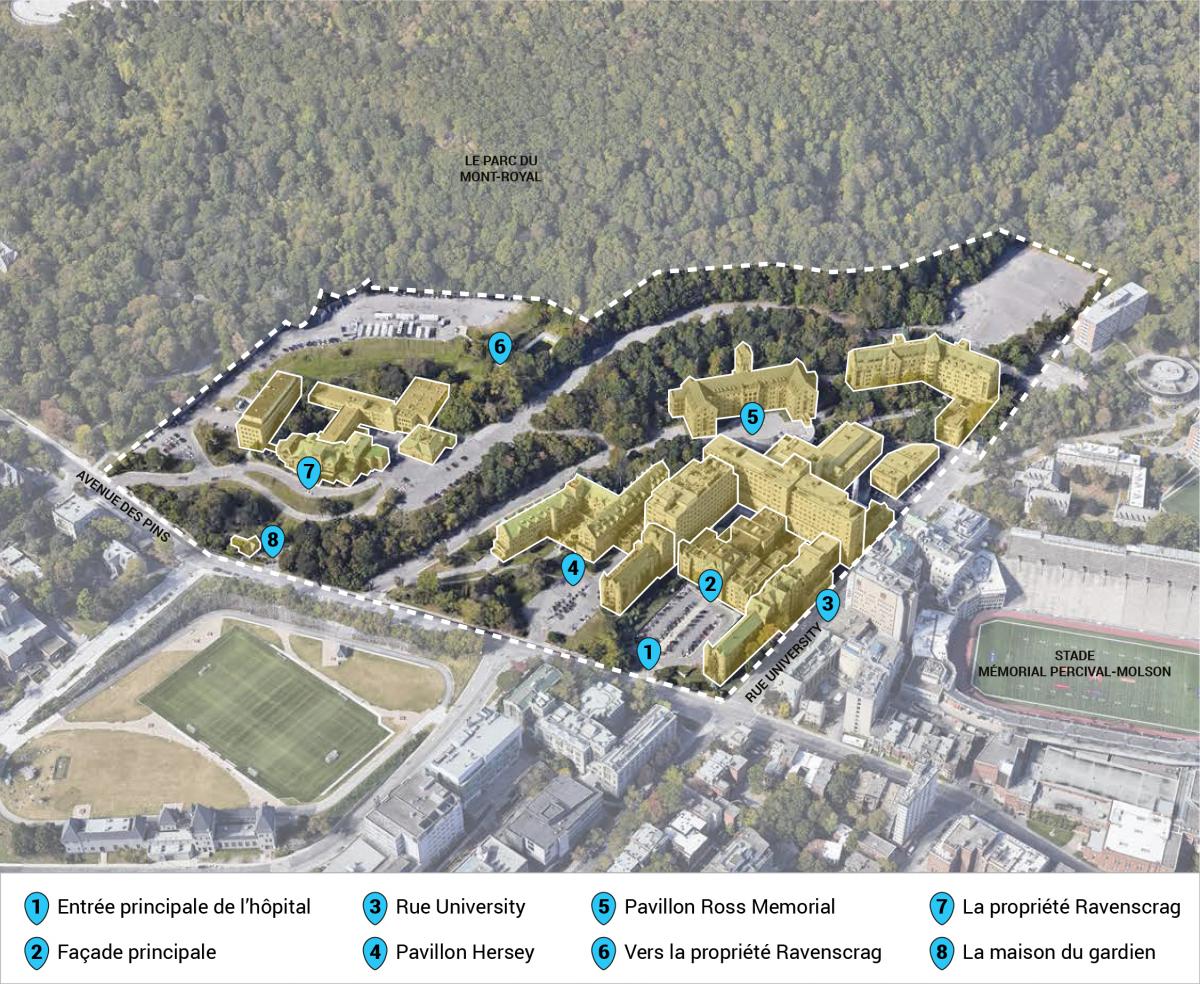

Source: Justin Bur

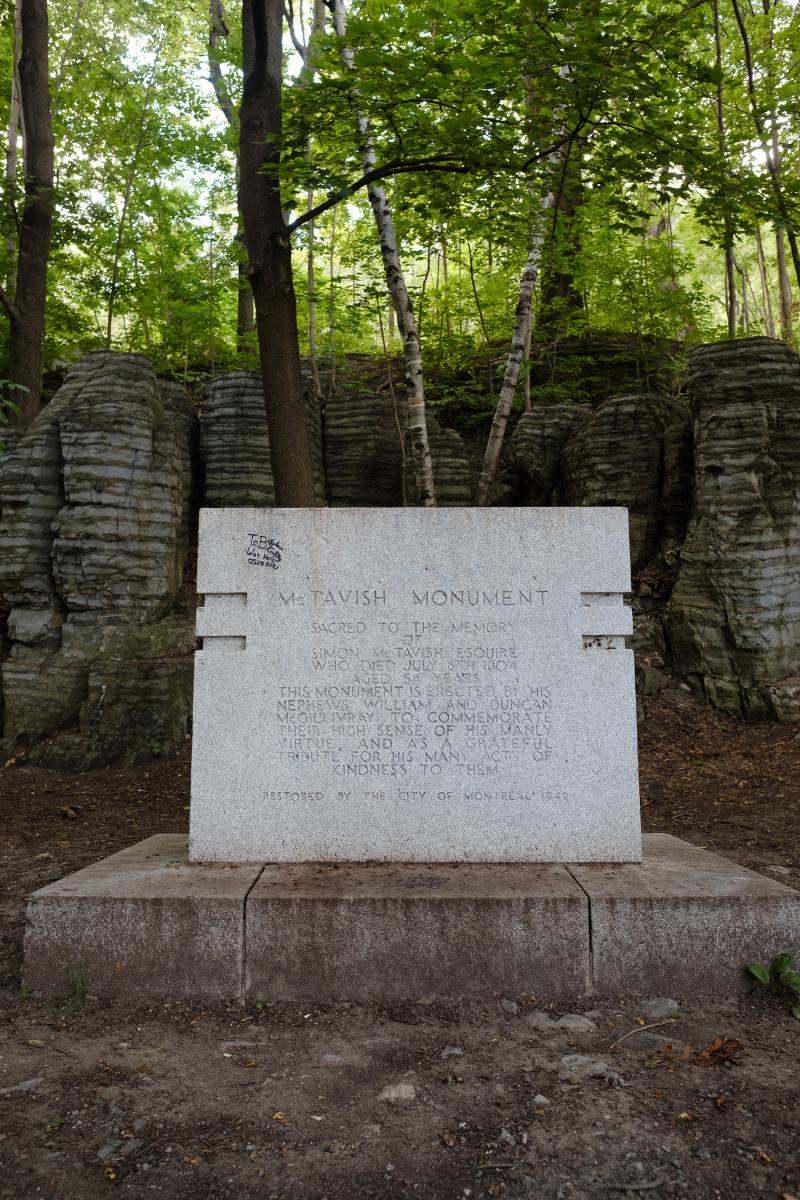

The Sulpicians, seigneurs of Montreal, put most of the mountain in private hands for the first time by granting it in 1708 to Pierre Raimbault, royal notary. The eastern limit of his vast concession corresponds to the central axis of the future hospital. After his death in 1740, his property was divided. About 40% of it was acquired in 1804 by fur trader Simon McTavish, who attempted to build a large mansion between Peel and McTavish streets, south of Pine Avenue. When he died in 1808, McTavish was buried in an isolated tomb high up on his property. His unfinished house was called the "haunted house" for decades.

Almost all of the old McTavish property north of Pine Avenue would eventually become part of Mount Royal Park in 1874. An exception was the property around Ravenscrag, the house built in 1863 by Hugh Allan. Allan succeeded where McTavish had failed, and even higher up the mountain. This property, donated in 1940 by the Allan family to the hospital, would become the Allan Memorial Institute.

From the eastern edge of the Allan property to the western side of the original hospital buildings, between Pine Avenue and the sharp rise in the park, lies another part of the old McTavish property. This was included in the park when it was created, then detached in 1889 to serve as the initial site for the hospital. However, the municipal drinking water reservoir (now hidden under Rutherford Park) was nearby and exposed. To allay fears that the presence of a hospital could contaminate the reservoir, the hospital buildings were moved to an adjacent lot. There would be no buildings on the initial site until 1907.

Between the intersection of Pine and Docteur-Penfield Avenues and the axis of Hutchison Street, a large rectangular space was occupied by the vast property of John Frothingham as well as other large residences. Head of a wholesale hardware company, Frothingham died in 1870 leaving the property to his daughter Louisa. The Frothingham home, known as Piedmont, was not targeted by expropriation for the park. On the other hand, a significant part of its grounds, including the west side of University Street, was to be taken for the park. Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted intended to create a main entrance to the park as a winding path starting from Pine Avenue near Doctor-Penfield. After Louisa Frothingham married John Henry Robinson Molson in 1873, the expropriation proceedings were suddenly stopped. Olmsted was furious. About fifteen years later, the Molsons were more open to selling the part of their land west of University Street to the founders of the hospital. It was here that the initial hospital was built.

2. Let's go closer to the main facade. The courtyard was initially a green space, converted into parking from the 1950s onward. The original hospital consisted of three almost independent wings, connected to each other only by overhead walkways (and later by tunnels). In the centre is the Administration Block; to the west, the Surgical Wing (of which only the southern part remains); and to the east, along University Street, the Medical Wing. This “pavilion plan” was chosen to separate the functions of the hospital and allow sunlight and fresh air to reach the premises. All the original buildings are constructed of Montreal grey limestone.

The architect of the original buildings was Henry Saxon Snell, an English expert in hospital design. He based the design on Scottish models, in particular the Royal Infirmary in Edinburgh, in accordance with the wishes of the hospital’s founders, two former leaders of the Canadian Pacific Railway of Scottish origin: George Stephen (Lord Mount Stephen) and Donald Alexander Smith (Lord Strathcona). Their monograms are present in bas-relief above the main entrance door: GS on the left and DAS on the right.

Behind the west wing, a modern high-rise building replaced part of one of the original buildings. This is the 1959 Medical Pavilion by the architectural firm of Barott, Marshall, Montgomery & Merrett.

If you turn and look south, on the other side of Pine Avenue, the building currently covered in safety netting is part of the McGill University campus. When it opened in 1911, it housed the Faculty of Medicine. Its three wings are precisely aligned with the hospital's three wings, though the symmetry is difficult to see today. It was another gift to the university by Lord Strathcona. After the construction of the new McIntyre Medical Sciences Building in 1965, this building was reassigned to dentistry.

It was originally possible to walk between the hospital pavilions. Over the years, the open spaces have gradually been occupied by vehicular paths and new buildings. And although all the pavilions are interconnected by interior corridors, they have not been accessible since the hospital was closed. As a result, the only way to get from one part of the site to another is by the city streets.

3. We now leave the courtyard and go up the hill on University Street.

University Street represents the eastern boundary of the grounds of the Royal Victoria Hospital. Going up the street, you pass between the original medical wing of the hospital and the Pathological Institute of McGill University, built in 1923 to plans by architect Percy Nobbs, very prolific on campus. A little higher, we notice the footbridge overhanging the street. It connects the hospital to the Montreal Neurological Institute (“The Neuro"), founded in 1934 by Dr. Penfield. Its building was designed by Ross & Macdonald, famous Canadian architects of the time (Dominion Square building, former Eaton’s store on Sainte-Catherine Street, Royal York Hotel in Toronto, Price building in Quebec, etc.). Since The Neuro is located across University Street, it is not part of the site under consultation. In addition, its activities will not be moved to the MUHC Glen site.

On the west side, the bridge connected with the end of the original east wing of the hospital. Since 1956, it terminates in the new Surgical Pavilion. Designed by architects Barrott, Marshall, Montgomery & Merrett, this modernist pavilion adopts the internal organization that one recognizes in other contemporary hospitals.

After the surgical pavilion, we come across the power house of 1900, still serving its original function. This attractive building by architect Andrew Taylor, echoing the Scottish castle theme of the main buildings, was added when the heating system was centralized.

Next is the 1931 laundry, designed by Ross & Macdonald. It is a very modest building for such grandiose architects. Its rear wall is curved to better fit into the limited space in front of the steep rise in the terrain just behind.

Finally, we arrive in front of the Women's Pavilion, originally the Montreal Maternity building, opened in 1926. Like its neighbor to the west (the Ross Pavilion, which we will see later), it was designed by the architects Stevens & Lee, specialists in hospital design. We are in front of the small back door for patients who arrived on foot, like us. The main entrance leads to the top floor, opposite the mountain, accessible by car via a long driveway leading up from Pine Avenue. That was the entrance for more affluent patients.

On the way back down, don't forget to notice the views of the city centre, even if the field of view is quite limited.

4. Back at the corner of Pine Avenue, turn right to return to the courtyard. Climbing up the grassy embankment above the underground garage exit (an addition from the 1980s), we can skirt the original west wing while admiring its large wrought-iron balconies.

We are now in front of the Hersey Pavilion from 1907, in another parking lot that was originally a grassy area. Mabel Hersey was the superintendent of nurses at the hospital for 30 years. This building, often referred to as the Nurses’ Residence, was designed to house student nurses who worked at the hospital. It is the first building on the land initially donated by the city.

Its architecture is intended to suggest a prestigious residence. The architects, brothers Edward and William S. Maxwell, were the designers of many large mansions on the mountainside, in addition to other monumental buildings such as train stations and banks. The Hersey Pavilion is the only part of the hospital designated as a National Historic site of Canada, as marked by the burgundy-colored commemorative plaque.

On the left, an addition from 1931 projects diagonally towards Pine Avenue. Its more stripped-down architecture indicates the change in taste brought about by modernism. The year of its design by architects Lawson & Little is engraved on one facade. After the hospital's nursing school closed in 1972, the Hersey Pavilion was reassigned to research functions.

5. Behind the 1931 wing is a path and a wide asphalt driveway leading upwards. We take the driveway to find ourselves in front of the Ross Memorial Pavilion. Located on the same level as the Women's Pavilion, this building by architects Stevens & Lee was opened in 1916. Its allure of a grand luxury hotel (the Chateau Style was fashionable for luxury hotels in Canada at the time) is reminiscent of its function: to accommodate paying patients in comfort. Unlike the main mission of the Royal Victoria, which was to provide free healthcare to all, this new pavilion was intended to meet the demand for a more luxurious environment for affluent patients, keeping them separate from the poor patients. Behind the tower, on the side of the building facing the mountain, was a tea garden.

The Ross Pavilion was almost a stand-alone hospital. Staff could circulate between it and the main hospital using a passage that ran from an upper story at the rear of the main hospital to the base of the steep slope under the Ross, completed by an elevator. Since the 1990s, the Centennial Pavilion has occupied the space at the foot of the slope, providing new connections between the buildings.

Who was the Ross that the pavilion commemorates? James Ross, a Scottish civil engineer responsible for the construction of several sections of the Canadian Pacific Railway, died in 1913. His son J. K. L. Ross donated hundreds of thousands of dollars for the erection of the pavilion.

6. Advance along the winding road which continues upward. It goes behind the Ross, ending up at the Women's Pavilion, which we have already seen from below. So let's leave the road by taking the stairway on the left. This stairway crosses the wall marking the boundary between the original hospital grounds and Hugh Allan's residence, Ravenscrag. The Ravenscrag property was acquired by the hospital in 1940.

At the top of the stairs, to the right, there is a swimming pool, on the site of the house's old vegetable garden. The pool was donated by Henry Morgan (who had just sold his chain of department stores to the Hudson's Bay Company) circa 1960, for the use of hospital staff. It has been out of service since the hospital moved in 2015.

Let's cross the lawn, going around the buildings on the left (east) side. We soon arrive in front of a greystone building which is not the main house. Its function is announced by the sculpture of a horse's head above the entrance. These are the old stables, built along with the house in 1861, and enlarged (including a redesign of the facade) in 1898. The two dates appear on either side of the horse's head.

7. Continue on the left to arrive in front of the house itself. The construction of Ravenscrag took place between 1861 and 1863 under the direction of Victor Roy, a young architect in the firm of William Spier. Its style, called Italianate or Italian Renaissance Revival, was often used at the time for the tasteful commercial buildings that were being built throughout Old Montreal (good examples can be found on Rue Sainte-Hélène). Hugh Allan, one of Canada's wealthiest men, of Scottish descent like so many others, had made his fortune mostly in transport. He ran a shipping company and was involved in several railway construction projects. The famous "Pacific Scandal", which brought down John A. Macdonald's government in 1873, was in large part Allan's fault: he had no qualms about handing out large contributions to cabinet ministers of the ruling Conservative Party in the hope of obtaining a major contract for the transcontinental railway.

It is said that from the top of the tower over the main entrance, Hugh Allan could see his ships arriving in the harbor and thus determine the moment of his departure to meet them on the pier. In any case, the view was magnificent.

After Hugh Allan's death in 1882, his eldest son, Hugh Montagu Allan, inherited the property and made it even more opulent; it was a place known for its balls and social events for the Montreal upper class. However, the socioeconomic changes after World War I made the maintenance of such a residence unsustainable. There weren't enough people willing to enter domestic service, the fashion for grand Victorian parties had passed, and the Allans moved to the Chateau luxury apartment building on Sherbrooke Street. Ravenscrag was donated to the Royal Victoria Hospital, which turned it into a psychiatric hospital, the Allan Memorial Institute.

Two major modern building additions were constructed in 1953 and 1962. The 1962 addition, the Irving Ludmer Pavilion (behind on the west side), is particularly imposing. Its architecture is resolutely modern but does not lack elegance and subtlety, which allows it to complement without overwhelming the historic residence.

8. Going down the slope towards the entrance gate, an essential outbuilding accompanying the original house (it is the interface between the city and the private domain), where all visitors had to pass muster. It was carefully restored in 1988 and transformed into offices. From here, turn to look at the house looming above: you have a good view of its facade silhouetted against the side of the mountain. The view downward is more restricted than it once was, now that the highrises of downtown Montreal block the river; nevertheless, it's still a good viewpoint.